Coding LLMs are here to stay: Here’s how to write your code so that LLMs can extend it

The potential of Large Language Models to write code is astonishing. But right now, it’s mostly just that—potential. If you can express to the language model precisely what you want in a concise fashion, the most powerful of the current generation models are surprisingly productive.

But as anyone who’s used these models will tell you, specifying precisely and concisely is the crux of the challenge. In fact, a considerable portion of a software engineer’s job is to take ambiguous or uninformed directives and rectify them with reality. Stated differently - reality tends to be far more complicated than the pristine simulation living in the minds of humans, and JIRA tickets tend to be compressed, biased representations of reality.

Large Language Models feel superhuman when the prompt given contains all the relevant information needed to perform the task, or contains information that enables systematic extrapolation about any other knowledge needed to complete the task. But LLMs can’t peer into your Neuralink and tell what you are thinking (yet). Instead, we need to structure our codebase in a way that gives a better view into our intuitions. As an added benefit, following these patterns will make your code more readable to humans as well.

How can we enable Large Language Models to systematically extrapolate from our codebase?

As soon as you are trying to prompt for something more interesting than a small shell script, things get difficult. Consider what you would feed into an LLM to have it make some arbitrary change to a medium to large codebase. Ideally, we could shovel the entire codebase, the codebases of any dependencies, and any related documentation into the context of our prompt. It’s unclear whether or not this will be practical in the near term, but this article will assume it’s not.

Constraints have bred innovation in the absence of infinite-context length technology. There’s a few strategies being tried right now, and to summarize most of them: they attempt to logically orchestrate various code search techniques to gather relevant context along with problem solving techniques in a feedback loop against running tests.

Anyone who’s tried this on a codebase of any reasonable complexity (and any realistic degree of quality) knows it gets messy quite quickly — to an unproductive degree.

One obvious conclusion from this could be that the underlying tech (LLMs with coding abilities) simply isn’t there yet. But I’m not convinced. I’ve seen too many first hand examples of GPT-4’s superhuman coding abilities in ideal conditions. The problem: we’re not giving it ideal conditions.

Imagine if you were given an average JIRA ticket specifying some task in a codebase for which you are completely unfamiliar. But instead of being given access to the codebase itself, you are provided only with the top 10-50 most “semantically relevant” blocks of code (each ~50 lines). Is it reasonable to expect you to be able to make the right changes to complete the task?

The limiting factor is the codebase itself — not the LLM capabilities or the context delivery mechanism

If GPT-4 can demonstrate superhuman coding abilities in ideal conditions, why don’t we try to make our realistic scenarios look more like ideal scenarios? Below, I’ve outlined how we can adapt our coding style with a few principles that allow large language models to perform better in extending medium to large codebases.

If we take the context length as a fundamental (for the time being) limitation, then we can design a coding style around this. Interestingly, there is a great amount of overlap between the principles that facilitate LLM extrapolation from code and the principles that facilitate human understanding of code.

1. Reduce complexity and ambiguity in the codebase

Unexperienced engineers solve simple problems with complex solutions, while great engineers solve complex problems with simple solutions. Complexity and ambiguity are roadblocks for LLMs as they are for humans. If your codebase is filled with nuanced patterns and hidden dependencies, it becomes much more difficult for an LLM to successfully extrapolate from your prompts.

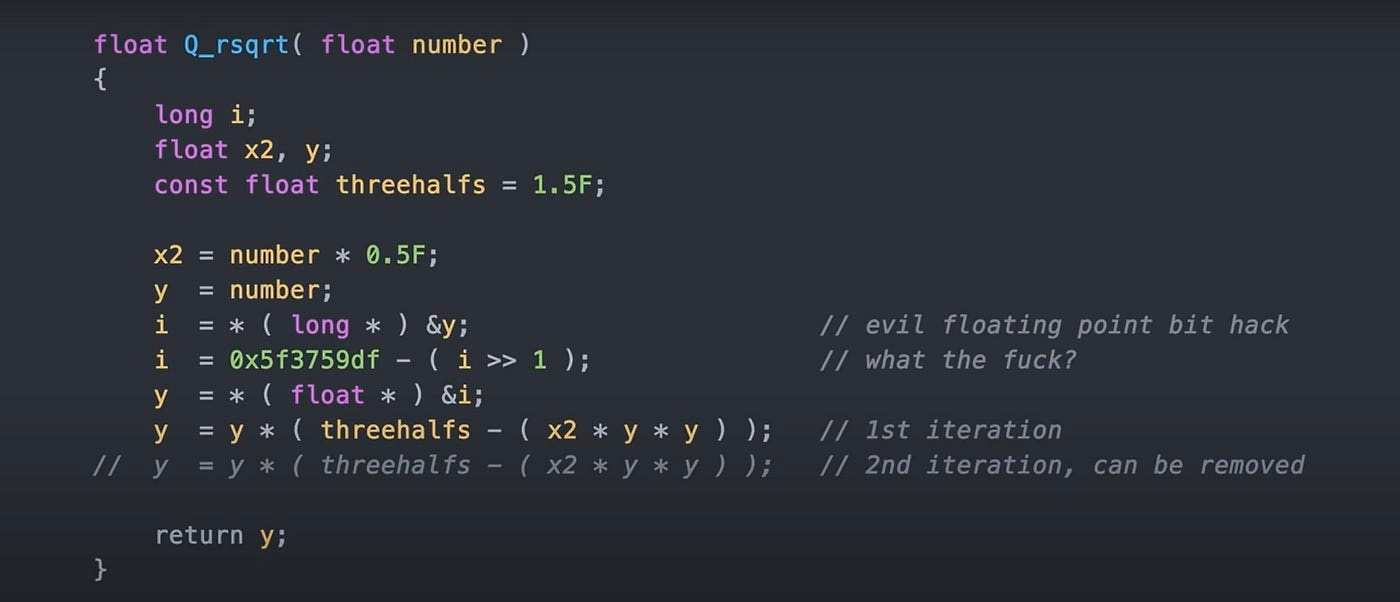

2. Employ widely used conventions and practices. Don’t use tricks and hacks

Current Large Language Models are trained on enormous quantities of code harvested from public repositories. This means they've seen a broad variety of coding styles, patterns, and conventions, but also that they're heavily biased towards the most common or "average" ways of doing things. If your codebase employs widely-used conventions and practices, it is more likely to be intuitively understood by the model, increasing the chance of successful interactions. If your tricks and hacks are unique and aren’t seen in the training corpus, it’s likely the model won’t be able to effectively extrapolate from or extend these code snippets.

How can we be innovative and solve problems that haven’t been solved before if we need to limit ourselves to run-of-the-mill tools or solutions? It’s a trade-off. For the 99% of software engineering that is secretly just dressed up CRUD plumbing, this advice probably applies.

3. Avoid referencing anything other than explicit inputs, and avoid causing any side effects other than producing explicit outputs

If the desired effect of running a function can be entirely reasoned about relative to input arguments, and the only relevant product is the function’s return value, then everything we need to understand how the function works is explicitly present in the lines of code of that function.

Another way of stating this is that we don’t need to search through any other part of the codebase to understand how the function works. In LLM land, this means that this function is a leaf node in the informational graph of concepts required to understand the codebase. We don’t need to perform any other embedding lookups. If we wanted the LLM to rewrite the function, we could likely achieve it with a single prompt with little additional context.

If instead the function contains a reference to a global variable, for example, then we may (in the extreme) need to lookup everywhere that global is used in order to ensure we are using it correctly. The importance of locally managing state as opposed to using global variables is outline in the next section.

4. Don’t hide logic or state updates

One of the most challenging aspects for an LLM when interpreting a codebase is the presence of hidden logic or obscured state updates. If the underlying logic is not immediately apparent from the prompt context, an LLM may make incorrect assumptions or predictions, and may incorrectly hallucinate how that logic may work.

As much as possible, code should aim to be explicit about its behavior and the changes it makes to the state of a system. In an ideal scenario, functions should perform a single, clearly defined operation and all state changes should be immediately visible.

For example, using helper functions that abstract away complex logic can make code easier to read and write, but it can also make it more difficult for an LLM to understand the full implications of a function call. If the definitions of these helper functions are not included in the prompt context, and they cause side effects on the state of the system that is hard to predict from the name of the function, LLMs (and also humans) may make errors when using this function.

A common bug that is caused by this is when a function takes an argument by reference (usually a list), modifies this argument, but produces an entirely separate return value. Developers using this function later on might not expect it to modify the input argument, causing a hard to track down bug (this is especially the case in languages where reference passing happens by default, like Python).

5. 'Don’t Repeat Yourself' can be Counterproductive

"Don’t Repeat Yourself" is a widely accepted principle in programming which encourages developers to eliminate redundancy by abstracting out repeated patterns into reusable functions or modules. While this can lead to more concise, maintainable code in many cases, it's worth considering how this practice can actually be counterproductive when we're aiming to create an LLM-friendly codebase.

The DRY principle can inadvertently lead to a higher degree of codebase complexity, abstraction, and indirection, which may confuse both LLMs and developers. These elements could hamper the LLM's ability to accurately understand and extrapolate from the codebase, especially when the reusable functions are more abstract and serve multiple use-cases.

In an LLM-friendly codebase, clarity should be prioritized over brevity. In some cases, this might mean repeating certain code blocks, as this repetition can make the logic and flow of the code more explicit, reducing the need for the LLM to infer or assume the effects of functions not included in the prompt. Each chunk of code then becomes a self-contained piece of logic, easier for both humans and LLMs to interpret without having to reference other parts of the codebase.

That said, this doesn't advocate for reckless code redundancy, which could lead to other problems such as inconsistency and reduced maintainability. Rather, it encourages a thoughtful approach to “Don’t Repeat Yourself”: consider when you are prematurely abstracting, and when that abstraction might hinder the explicitness and readability of the code, particularly in the context of LLMs.

6. Unit tests serve as practical specifications for LLMs, so use test driven development

The advertised purpose of unit testing is to prevent regressions, but there is another great side effect. If written correctly, unit tests serve as documentation: they should illustrative examples of all the ways a module can be used.

If you take the approach of test driven development and write tests before you implement the unit, you force yourself to precisely specify its behavior. In other words, you’re taking time to build the perfect prompt. By supplying these unit tests as prompt context, LLMs can really shine: all the tools they need are provided, and hallucination is minimized because you’ve biased the model in the correct ways.

Further, this approach enables you to use systems that are being developed to refine LLM produced code implementations based on unit tests. Tests are first supplied to the LLM, which produces a unit implementation. Then, we run those tests (using an interpreter) against the implementation, and record any errors or test failures. Next, we prompt the LLM to rewrite the code based on those results.

This process can be run in a loop, and is surprisingly effective if the quality of the unit tests is high (they conform to many of the other principles mentioned in this article) and their assumptions are accurate.

As we continue to develop these large language models and experiment with using them in various contexts, we're likely to learn more about what works best. However, these principles offer a starting point. Adapting our coding styles in these ways can both improve the performance of LLMs and make our codebases easier for humans to work with.